Home QGraph

High Velocity Data Ingestion: Lessons We Learnt

Summary

This article describes our experience at QGraph about high velocity data ingestion.

It describes how we built version 1 of our data ingestion system (in a day), and how

we evolved it over the next 2 years in response to increasingly high velocity of data.

The actions we took look simple in retrospect, but they were not obvious when

we were implementing them. There were many steps which we took, only to roll them back.

If you think we are missing some basic ideas for the improvement, kindly contact me.

The problem statement

Various of QGraph SDKs (for android, iOS and web) send semi structured data about the

users to QGraph web servers. Data is sent in JSON format via HTTP POST requests. Data is typically

small in size: usually smaller than 1KB, though sometimes it can go as high as 20KB. We want the data

to be available for use for other systems within a matter of seconds.

A typical POST body looks like this:

{

"userId": 123123123123,

"appId": 63adf2dadf2d344,

"name": "Vivek Pandey",

"hobbies": ["Chess", "Mathematics", "Algorithms"]

}

We decided the ingestion system needs to write this data to MongoDB1.

How do we design and implement a high performance and low cost architecture to achieve this?

What follows is the description of the process of iterative improvement that we

followed for over an year to make ever improved data ingestion system.

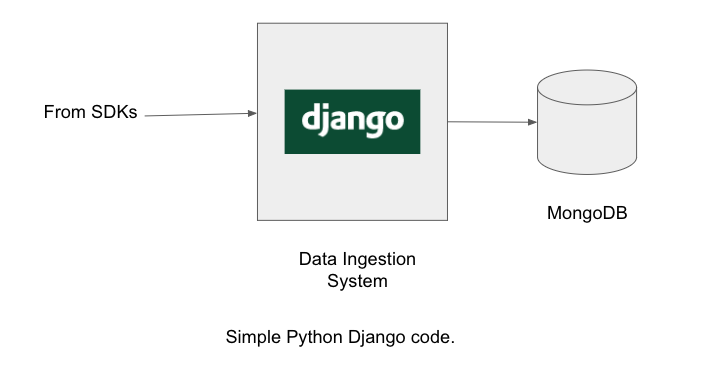

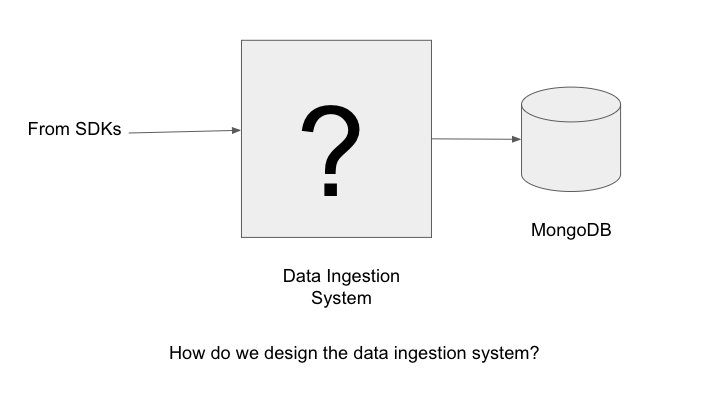

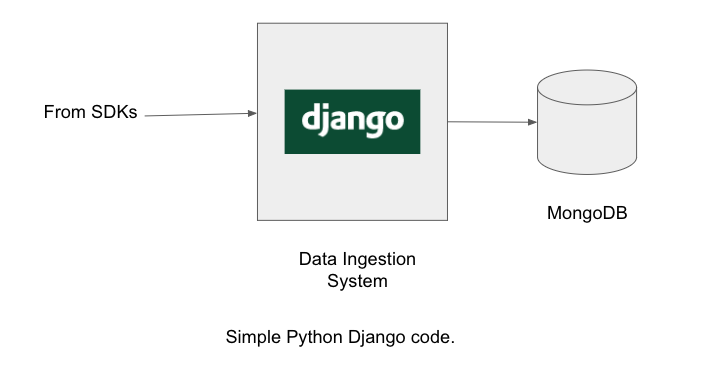

The beginning: no traffic, no complexity

We were just starting out and had no visibility into scaling issues that may arise in

future. We did not try to predict them either. We wrote a simple server in Django

REST framework, which connected to MongoDB on each request and fired a query to

store the data.

This served us well during initial testing, however things started to go bad as soon

as the rubber hit the road, i.e. the first client went live.

The rubber hit the road

We saw that in times of peak load, data ingestion was not working properly: it was

taking too long to connect to MongoDB and requests were timing out. This was leading

to data loss.

This is a common problem: During high load, all the components in the chain

are stressed, and the one of the component gives in. One could make the weakest link

stronger, but one can do better: introduce a buffer before the weakest component.

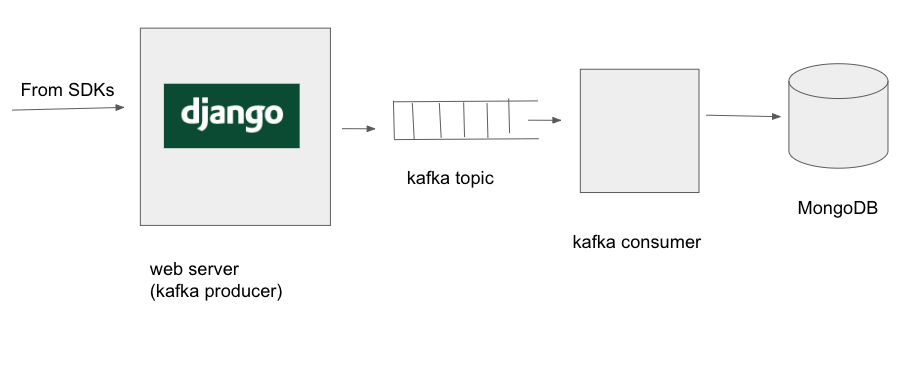

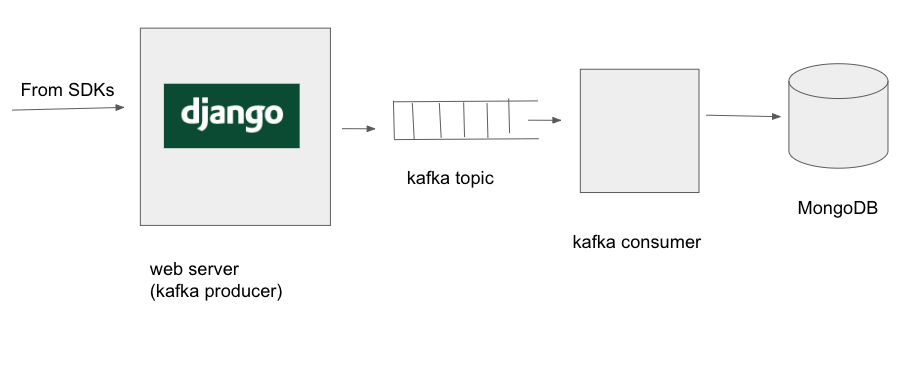

Since in our case, it was the MongoDB which was unable to ingest data fast enough, we decided

to put a messaging queue before MongoDB system. Enter Kafka.

Why Kafka? Well Google searches led us to believe this is the tool most suitable for

our purposes. And we also felt that the fact that we use Kafka will make prospective

employees to want to us to join us.

Hah.

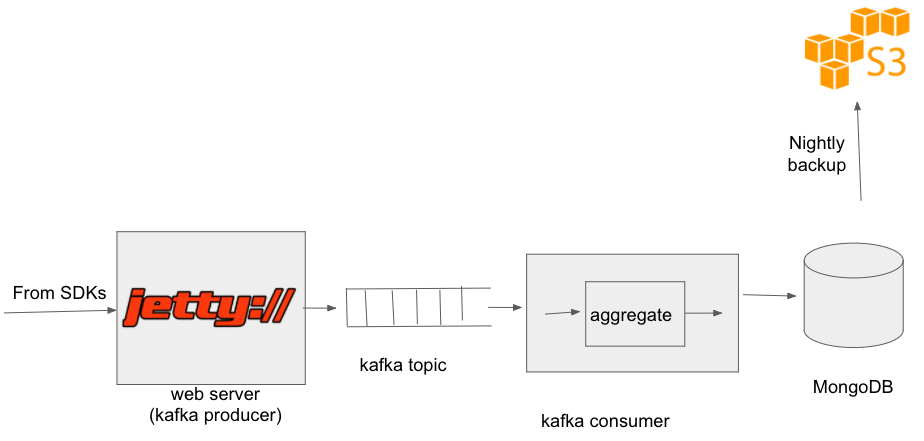

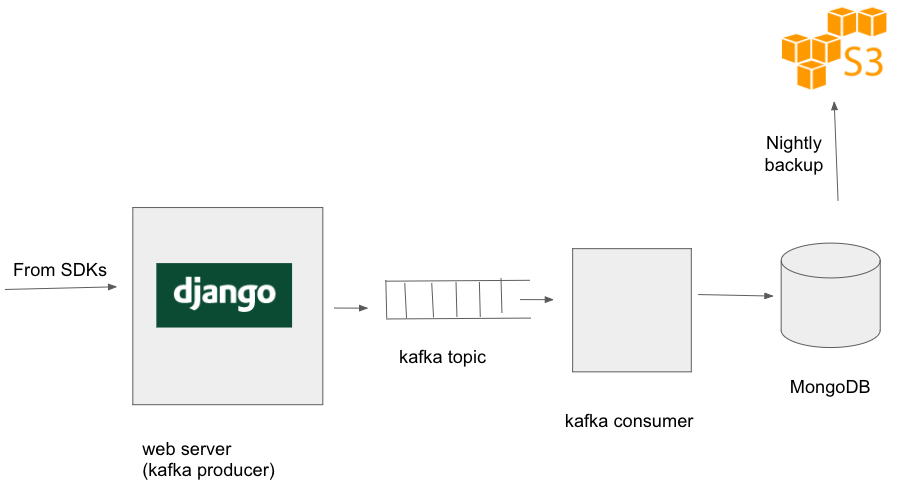

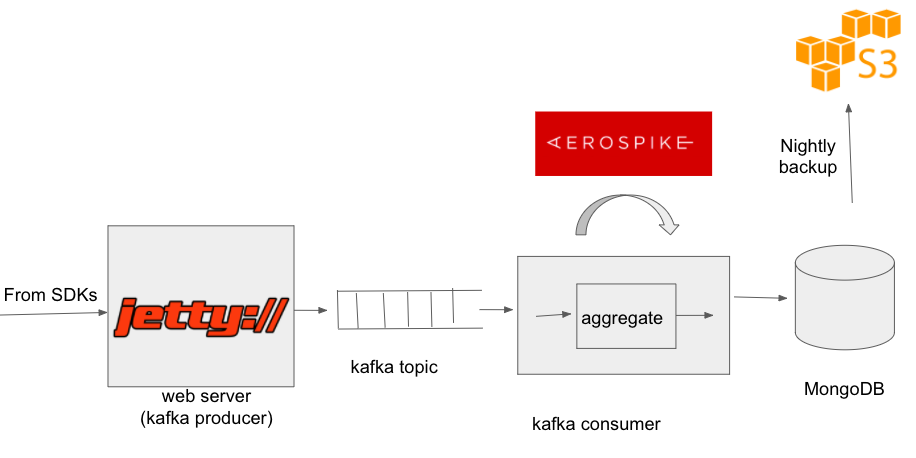

So, now, the webserver wrote data to kafka topics. And we wrote a kafka consumer which

read the data from the kafka topic and wrote it MongoDB. So, the architecture now

looked like the following:

Why is writing to kafka better than writing to MongoDB? It is because when you are

writing to kafka, you are writing to the end of a file, which is hightly efficient.

Unlike MongoDB (or any database), there are no indexes to be maintained, no

degragmentations to be compacted, and no queries to be answered. Produces produce

and consumers consumer, that is all.

Now, at the times of peak loads, requests get stored in Kafka while the consumer,

limited by the MongoDB, processes them. Thus, at peak time, it takes a few minutes

before the data gets to MongoDB. However, it is fine, because these peaks

themselves last only a few seconds or minutes, and occur only a few times a day.

We spent some time in choosing optimal settings for kakfa. In particular, we set the

batch size, maximum latency and compression as per our needs.

Car Connection Pooling please!

OK. This is fairly basic. We were not using connection pooling so far. For each

update to the database, a connection was opened, request was made and the connection

was closed. We moved to connection pooling, and this led to slight decrease in

CPU utilization of mongo machine, and a large decrease in the default mongo logging

(which logs one line per connection open/close).

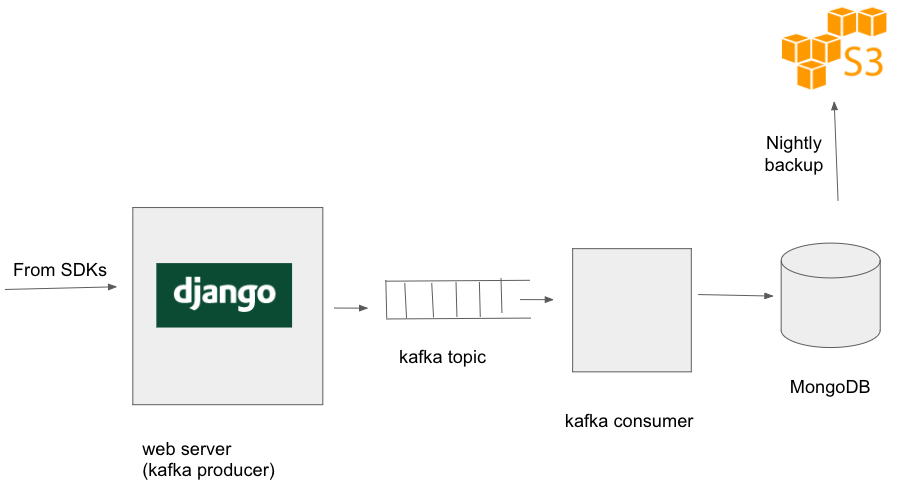

Back it up

Once we had a few clients, we started worrying about data loss. What if the Mongo machine

went down, never to come up again? Or else we somehow corrupted the data beyond repair?

Or if, by mistake someone deleted an entire customer's database?

To guard against such occurrences, we started taking daily backups of our database

to S3. As time went, daily backups became too heavy, and then we started daily

incremental backups, i.e. we take backup of only that part of the data which

is either new or modified. This is what the architecture looks like after this.

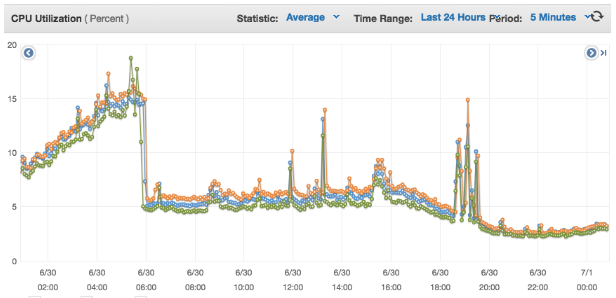

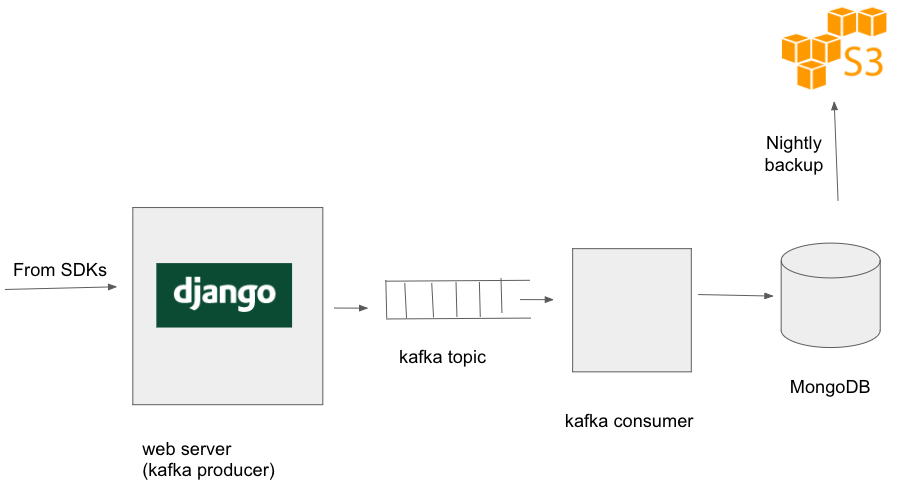

Move to Java for web servers

With using Kafka as a buffer between the web server and mongo machines, the system

was quite stable. However, we were using a fleet of webservers, and thought we could

bring down the fleet size by using Java as the language rather than Python. Python

had helped us getting everything running quickly, but now we required more performance.

Thankfully, the web server code was pretty straightforward: just read the post body,

do some simple validations and put a message in a kafka topic. We chose Jetty as

the framework of choice (partly because in my previous company people had worked on

Jetty based web servers). As we had expected (and described in detail

here),

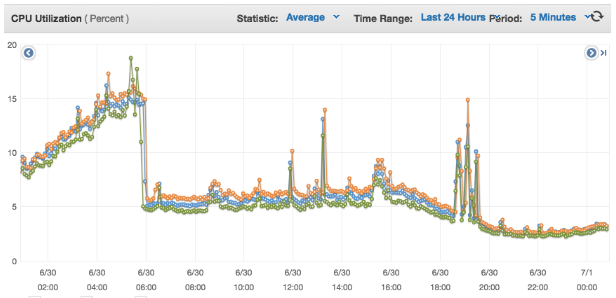

we reduced CPU utilization of our web servers drastically:

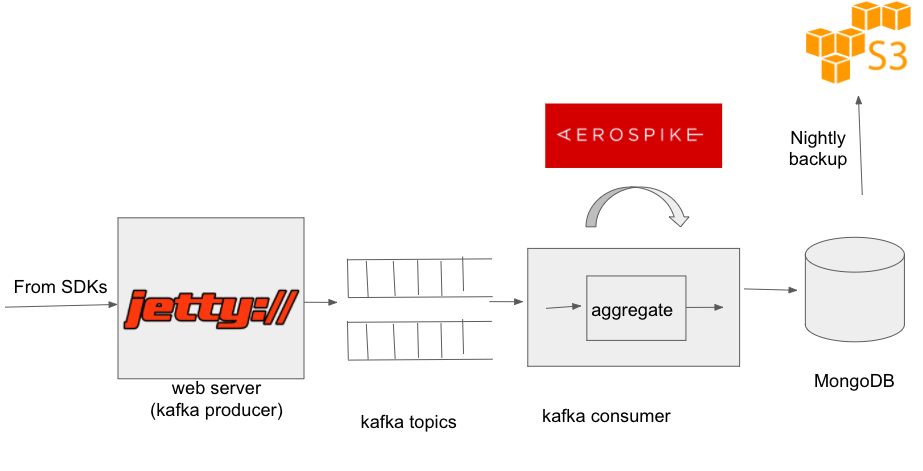

Now, our architecture looked like:

Things went fine for a few months, when we started facing a fresh problem. The

problem was that periodically, kafka consumer was way (sometimes hours) behind

the producer, i.e. we were unable to put data to MongoDB as the rate at which

was arriving. Again, this happened when there was a spike in the incoming

data rate. It usually happened when a large client sent push notifications to

all their users. In that case a large number of users open the app within a

small window of time, causing an increase in the event rate on our servers. Couple

it with the fact that MongoDB could be getting queried by some other subsystems

while it is ingesting data at a high rate. In such a situation, both the ingestion

and the querying came to a standstill.

We could always move to mongo machines with more memory (so that more indexes

could be in-memory), but turns out that there was a software solution to keep

us going:

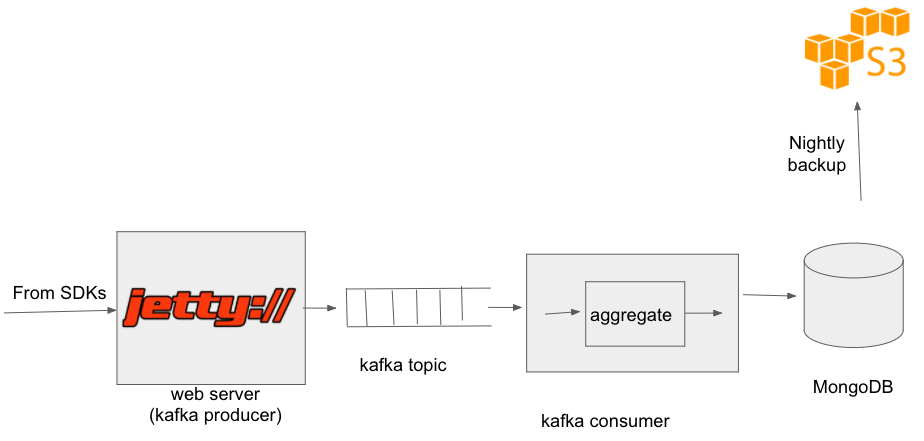

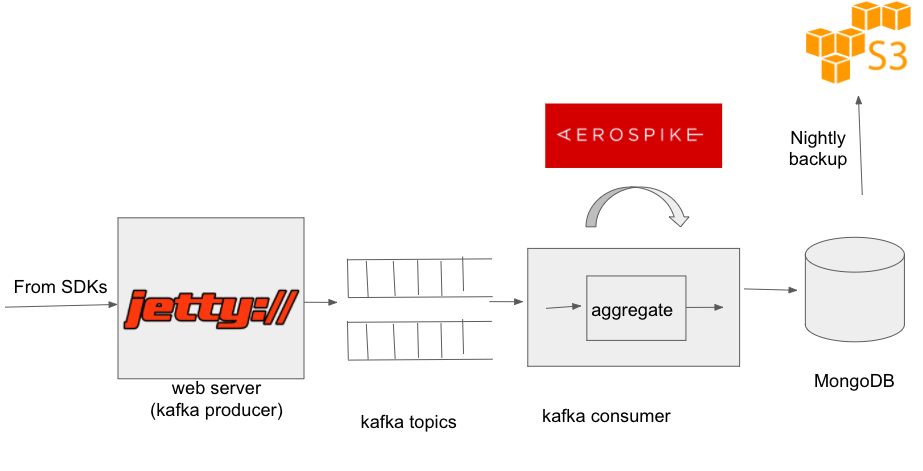

Aggregating the queries

We realized that bulk operations to mongo were more performant that individual

operations.

We wrote a module, called mongo query aggregator, which provide similar

interface to other mongo drivers, but which aggregated the write queries and fired

them to mongo either when threshold number of queries were collected or when a threshold

amount of time (few hundres of milliseconds) had elapsed. This again reduced CPU

utilization of mongo and mongo was able to ingestion spiked data in a graceful way.

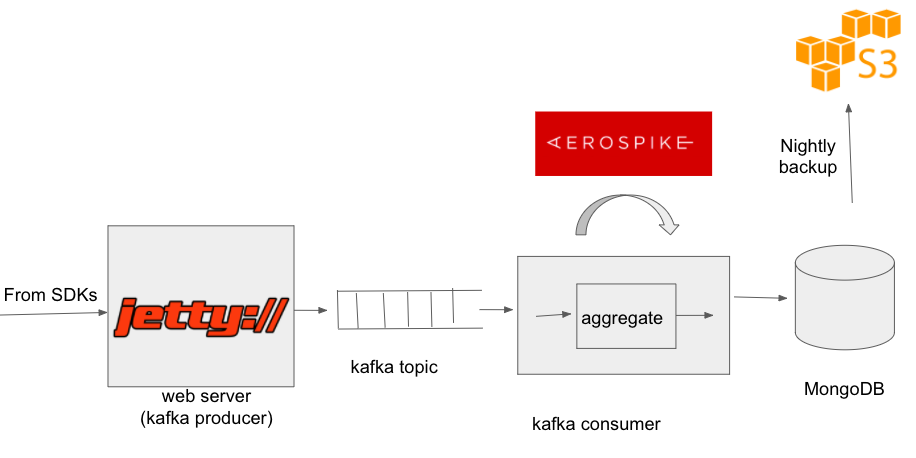

After introducing query aggregator, our architecture looked like this:

We released our mongo query aggregator on github. You can access it

here

To install it, simply run

pip install moquag

on your system

Caching layer before MongoDB

As you may have noticed till now: MongoDB has been continually the weak point all

along. That is expected, since MongoDB is a busy system: on the one hand it is ingesting

data in realtime, on the other hand it is being queried by dozens of other subsystems.

Thus, a large part of the effort is around reducing the laod to MongoDB. We have done

a lot of work around reducing the readread query workload of MongoDB, but that is a separate

topic.

A few months after the previous change, as the ingestion rate and query rate increased

again we started having the kafka lag problems again: at times, consumer would be behind

the producer by as much as a few hours. Incidence of such problems rose from infrequent (once

every four weeks) to mildly frequent (once a week). At the time of large read queries,

the ingestion system would be too slow and it would take a lot of time for data

to reach from kafka to MongoDB.

Fortunately, we had a weapon to attack this problem. That weapon is the CS engineers'

favorite weapon: Caching.

We realized that a lot of data that we were getting was repeated data. For a given

user, we got his profile information as many times as he did some action. The profile

information that we got contained information like the name, email or the city

of the user. This information tends to change very slowly, but we wrote it to MongoDB

repeatedly. To reduce the query rate to MongoDB, we put an aerospike cache in front of

MongoDB. As we write some information to MongoDB, we also wrote it to aerospike. However,

before writing info to MongoDB, we checked in aerospike if the same information

was present already. If yes, we did not bother to write the information in MongoDB.

This optimization reduced the MongoDB queries by around 60%.

Along the way we also realized that not all data is equal. For some types of data

it was important to get it to MongoDB as soon as possible. Other type of data could wait.

Thus, we started from putting data in two different queues from the producer. When

there was delay in getting data to Mongo, we could shutdown the consumption of lower

priority queue, thus ensuring that high priority data reaches mongo on time. Once the

peak traffic was over, we would start consuming the lower priority queue.

This is data ingestion story till now. Our system continues to evolve.

Upcoming action items and problems to be resolved

Following are some action items we can take up in future to further optimize

our data ingestion system

-

Use auto scaling: Boot more web server machines during heavy load and shut them

down during low load. With AWS supporting

per second pricing rather than hourly pricing, this idea will be even more effective.

-

Currently, our Jetty server does some preliminary validation on the incoming

data, and post this validation, puts the message in the kafka queue. In the

interest of lower latencies, we can put the POST body directly on the kafka

queue (without validation). The consumer can take care of validaton and reject

the message if it fails validation. Further, if the only job of web server is to put the POST body to

a queue, do we need Jetty for that? Can we have an nginx module to do that? If

that is possible, our web server will be even more efficient and low latency.

-

While most of the requests have response times of <2ms, averge respones times

of our servers are >10ms. The reason is that some requests arbitrarily take

a large amount of time. We have not yet been able to figure why is that so.

Data ingestion system began with a simple 30 line django code, and by now it has

expanded to thousands of lines of code, with multiple systems running on

various machines. When we began we did not know how the system will evolve, and

we did not try to predict the problems that would happen. However, we kept our

eyes and ears open and solved the problem as they came.

Footnotes

1. Yes, I know MongoDB can lose data. I know I should use MySQL. Thanks for your concern.