During the second half of 2018, I had the good fortune of living in Taiwan. Living in Taiwan exposed me to the wonderful Chinese language, and made me realise that all the languages that I know (Hindi, English, a bit of Kannada ) or have attempted to learn but forgotten now (German, Bengali) are pretty much same. They just name things differently and have minor grammar variations. I realised that there can be a completely different way to design a language. It is like learning Haskell or Lisp after having known only C or Java.

In this article I write about how Chinese is different from Indian or European languages {Hindi, English, Kannada, Tamil, German....}, and some interesting factoids that I found out. Note that this article is for those who do not know any Chinese. If you know Chinese you will likely find many flaws in this article, which you can let me know and then I can improve.

In most languages, there is an alphabet composed of letters (A, B, C, or क, ख, ग). Letters don't have meanings. Letters combine in various ways to form words. Words have meanings: we know what is meant by "mountain", "man" or "sea".

In Chinese, there are no alphabets or words. There are just characters. Each character represents something. Eg. 山 is mountain, 男 is man and 海 is sea.

Now, the way symbols are drawn is often related to the thing or concept it represents. 山, the mountain, contains three peaks; 人, the person, looks like a person. Perhaps you can spot an elephant in 象, or agree that 木 looks like a tree, or 口 is a mouth or opening. In rain 雨 you see water droplets, and umbrella 傘 can be seen to give shadow to four people.

It is not always possible to draw everything, so sometimes chinese characters become an exercise in abstract art. For instance 座 is seat, where you can see two people 人 seated. 广 often symbolises an enclosure, or space , like 座 is seat, 廳 is hall, 廠 is factory. An enclosing square 口 is often used for an area (often land), like 國 is country and 園 is garden. 田 is farmland or field (you can see land divided in various parts), and fruit is 果 which is a combination of 田 (farm) and 木 (tree).

In some cases, characters are composed of two parts: a radical element and a pronunciation hint. For instance 氵denotes water or liquid and 汁 is juice, 酒 is wine, 汗 is perspiration, 江 is river and 湖 is lake. In all these characters, right side is used as a hint for pronunciation of the characters. For instance 江 is jiang and 工 is gong; 酒 is jiu and 酉 is you.

Some pictograms can be funny: 人 is person and 囚, with an enclosed person, is prison. 女 is woman, 男 is man and 嬲, with two men and a woman is to flirt. 姦, with three women, is adultery.

If you start having a symbol for each new thing that you encounter, you will have so many symbols that you will not be able to memorise them. So, many concepts or things which are one word in Hindi or English, are a group of characters in Chinese. For instance socialism is 社會主義 which literally means "common production primary virtue". So when you encounter these 4 characters together, you have to get the meaning of these characters as a whole. 開 is open and 關 is closed (Do you see a door in both these characters?) and so a switch is 開關. Restaurant is 飯店, which is literally "rice shop".

In the previous section, when I told you that 田 is farm or 木 is tree, I did not need to write about how they are spoken. And you don't have an idea of how to speak them. This is not possible in Hindi or English which are phonetic languages.

As a result, you can almost read Chinese if you just know the meaning of various characters. The places where you would get stuck is proper nouns like names of the person or the cities. As in Indian languages, names have meanings. So you would read 英文是台灣總統 as "Flower language is Taiwan President" rather than "Ing Wen is Taiwan President"

This is funny: you can read a Chinese newspaper or a book, but you can't talk to a person in Chinese!

So, what it means is that in other languages, the flow of understanding is:

written symbols -----> pronunciation -----> meaning

In Chinese the flow of understanding is

----->pronunciation

/

/

/

written symbols

\

\

\

----->meaning

The funny thing happens other way too. In English, if you can speak something, you can write it too. You may get the spelling a bit wrong, but you will be able to communicate via writing. Not so in Chinese. A friend of mine told me that once, during a discussion, they were talking about "interrupts" (as in processor interrupts in computer science). They all knew how to speak it, but none of them knew how to write it.

So you can choose to learn either the pronunciation or meaning without learning the other.

I read somewhere that when Chinese people initially came in contact with western languages, they were ignorant of the idea of phonetic language and thus they would try memorise meanings of the words as a whole: thus they would look at the word "table" as a whole and memorize what it means, rather than understanding that "table" is composed of 5 letters and it is better to memorize the pronunciation rather than the design of the word "table".

Chinese is a "tonal" language. What it means is that the tone in which you say something matters. Now what is a tone? Think like this: You say the statement "You are going there.", differently from the question "You are going there?" to an assertive "You are going there". In English we write them identically, but we speak them differently: in different tones.

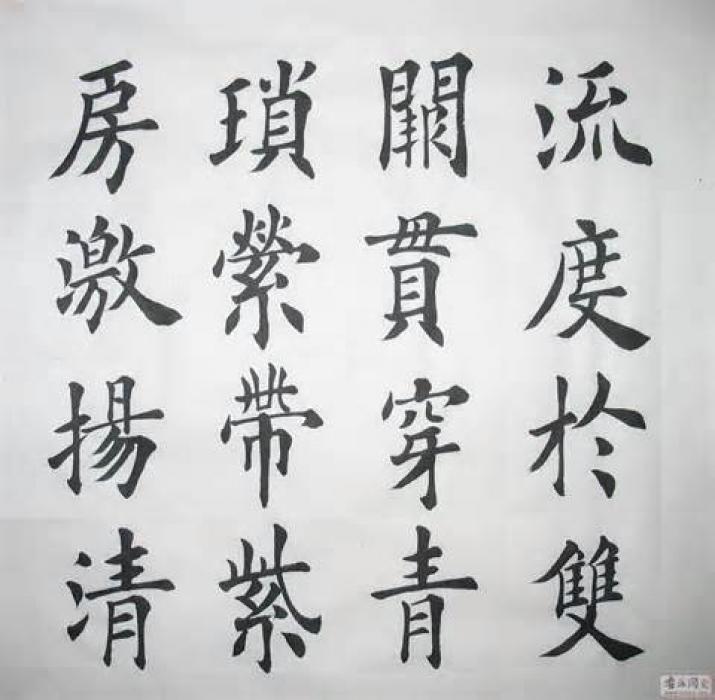

In Chinese, different tones may mean completely different words and may be written completely differently. Thus, to be understood, you have to speak in correct tone. There are 4 tones in Chinese language and despite watching many videos about this, I could never get it in practice. Many Chinese people in my office generously helped me, but I could hardly ever get myself understood by Chinese people. For fun, here is a poem which uses tones extensively. My Chinese friend could understand it without problem:

It is not there is something inherently hard about pronouncing the tones differently. It is just that Indians or Europeans don't have that concept. To Chinese people, the 4 tones are very clear and there is no confusion. On the other hand they found it hard to distinguish Hindi द from ड or क from ख.

Further, I could find several Europeans and some Indians in Taiwan who speak Chinese (well, Mandarin to be precise, but let's not go there) fluently. So, this not an unsurmountable task even for someone who learns the language at an advanced age.

While the number of characters is huge and learning them is daunting, there are no hard grammar rules to be learnt.

In English, plurals of I, you, he is respectively we, you, they. In Chinese, the plurals of 我(I), 您 (you), 他 (he) is respectively 我們, 您們, 他們. Just add 們 and pluralise!

In English, I go; we go; he goes. In Chinese everyone just 去. 我去, 您去, 他去. I am not sure about tenses: I go, I went, I had gone, I had been going etc, but I have a vague understanding that the concepts are also quite simple in Chinese.

Similar is the case with ordinals: first, second and third have no similarly to one, two and three. It is only from four-fourth, five-fifth that the similarity starts. In Chinese, it is consistent: one, two, three, four are 一, 二, 三, 四 and first, second, third, fourth are 第一, 第二, 第三, 第四.

This logical simplicity, surprisingly, has a disadvantage to it. If "I go", but "he goes", then, in a conversation, if I just hear "go", and miss out on "I", I can deduce that the subject can't be he/she/it. Similarly, tenses in Chinese are sufficiently close to each other that one relies on other words and context to get the complete meaning.

So, to understand a text or speech well, you have to be aware of the context. This is contrast with English or Hindi where there is sufficient redundancy and you can afford to miss on larger part of the speech.

Transliterating English words in Hindi or vice versa is very easy. विवेक पाण्डेय is easily written as Vivek Pandey and Donald Trump is easily written as डोनाल्ड ट्रंप. We don't even think about it.

Now welcome to Chinese! Firstly, Chinese to English is hard. Chinese is tonal language, and there is no concept of tones in English. So, people have made some all sorts of conventions. Some people denote tones with auxiliary symbols. Like 媽, 麻, 馬, 罵 are written as mā, má, mǎ, mà respectively. If you want to transliterate to Hindi, no one has established such conventions. And some people have used less used English letters to denote specific chinese pronunciations: Eg. in Xi Jinping, "X" is pronounced as "sh", and in Qing, "Q" is pronounced as "ch". There is a city in China called Chongqing (重庆). Now 'ch' of 'q' is slightly different from 'ch' of 'ch', so rather than writing it as Chongching, we write it as Chongqing.

Other way is also fraught with difficulties. Sounds in English (or Hindi) and Chinese are completely different. For some sounds in English, you have multiple ways to write them Chinese. Eg. from previous example "ma" could be written as 媽, 麻, 馬 or 罵. For some other sounds, there may be no close enough counterpart. I found a "Roosevelt" Road in Taipei, which was written as 羅斯福 in Chinese. 羅斯福 is literally spoken like "luo-si-fu".

This difficulty of transliterating has an advantage for Chinese people! Since transliteration is hard (even making English sounds is hard for Chinese), it forces them to arrive at Chinese translations of all the western origin words (which are a plenty in science and technology). Thus, in their conversations, English content is very small.

For instance, Hindi speaking people use the words "computer", "keyboard", "mouse", "mobile phone" in their conversations even when they are talking in Hindi. Even while writing they would just write those words as कंप्यूटर, कीबोर्ड , माउस, मोबाइल फोन. In Chinese they cannot transliterate because of sound differences. So, they have translated computer to 電腦 (electric brain), keyboard to 鍵盤 (key plate), mouse to 电脑鼠标 (electric brain rat label) and mobile phone to 移動電話 (shift move electric word).

Thus, their day to day conversation remains "pure", where we Indians find would find hard to communicate with each other if we were to decide not to use English words.

Finally, Chinese characters are hard to write. While some are simple: 大, 木, 日 or 月, others are complex: 聽 is to hear, 灣 is the "wan" in Taiwan, 摩 is to touch. Some are monstrous like these:

A special character of these characters is that one character can contain other characters(!). For instance, 德 (moral) contains 十(ten), a rotated 目(eye) and 心 (heart). Thus, with relatively small number of basic characters, one can form a very large number of characters.

Each characters must be written in a specific stroke order, and it can be hard to get it right:

Some characters are so complex that one often has to increase the font size to be able to see the character clearly. I bet you needed to do this for many characters in this article.

Government in mainland China decided that the difficulty of writing the characters was affecting their literacy rates so it decided to simplify the characters. Many characters got simplified: 國 became 国, 門 became 门 and 聽 became 听. While proponents of simplified characters claim that language should be simple to write, proponents of traditional characters see characters as a part of culture that should not be tampered. Traditionalists point out that character for love 愛 contained within it a heart 心, but in simplified chinese, it becomes 爱 which is devoid of heart. Simplification proponent point out that the heart has not vanished, it has just become shortened to a line; and that characters have been changing all through the history.

After learning the traditional characters, I personally find simplified characters bland and lacking in aesthetics.

I challenged many people to write various characters without electronic help and it was easy to trip most of them. They agree that it is indeed a bit of hassle to write Chinese by hand, but that has little practical impact because most writing is in electronic form.

Overall, learning Chinese has been a very pleasant experience for me and I continue to learn Chinese and enjoy the beauty of the characters!